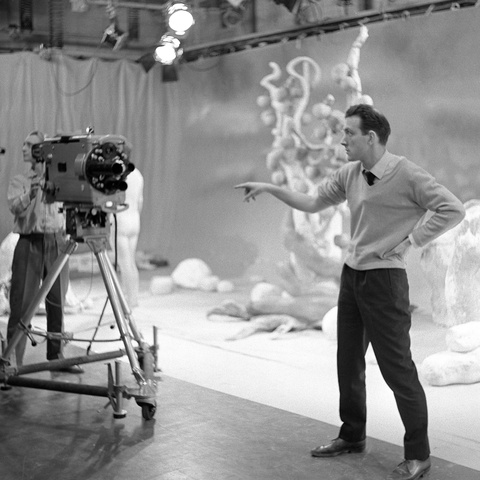

Fot: Zygmunt Januszewski/TVP/EAST NEWS Teatr Telewizji, 19.03.1962 - Historia od poczatku, rez. Konrad Swinarski N/Z: rezyser Konrad Swinarski J-2642-5

Piotr Zaczkowski writes about Konrad Swinarski, the patron of the festival and his artwork.

From the notes on Konrad Swinarski: Directing the city

The last trains departed from Katowice on 26 January 1945. A number of exiles fled. Among them those afraid of the approaching Red Army. They were said to have left hurriedly, casting off their duvets and blankets aside, leaving clothes and even food reserves behind. Aneta and Mieczysław Cybińscy went down to the basement of the house at Grünstrasse 4. They were accompanied by relatives they had provided with shelter several years before – Irmgarda Swinarska and her 16-year-old son Konrad.

The following day, the inhabitants of Katowice were woken up by the ever-louder detonation of shells. Soviet tanks were advancing from the side of Zawodzie. At noon, the inhabitants of the centre of Katowice could hear the thumping steps, voices and the cracking of windows. After plundering the shops and warehouses, the soldiers came to rob the apartments. They raped women. Drunken soldiers started fires. The fire consumed several houses at today’s ul. Pocztowa and św. Jana.

When in 1964 Konrad produced “Pluskwa” at Berlin’s Schillertheater, the critics would cry that he stirred madness in theatre. 240 actors. Special effects. Regular effects. A refrigerated car with frozen Prisypkin drove onto the stage. Restaurants burning. Orchestras marching. A choir of Soviet soldiers on the stage, clad in the uniforms leased from a film costume storehouse. As a line of soldiers moved on, 1945 came to the spectators’ minds. Some were petrified in their comfortable seats.

If the premiere of Hamlet was held at the Kraków’s Stary Theatre, the military would have been stationed outside of the walls of Elsinore as Konrad Swinarski wanted the brutish soldiers to set up a camp at the Szczepański square. Plenty of horses, cars loaded with looted goods: poultry, feather blankets and pots. In the finale, the soldiers would invade the theatre from all sides: from within the stage and from the auditorium. Jerzy Skarżyński explained director’s intentions: “A gang of sorts, an army of brutish soldiers would enter the theatre; they won and so everything belongs to them. Soon, they might start taking watches and wallets from the audience…”

Tadeusz Nyczek argues that the Kraków Hamlet could be interpreted as “a bleak and miserable history of a satellite state, suffering from pressure and then an invasion mounted by a neighbouring state ruled by ruthless Fortinbras, and the continuous presence of the army, camping at the Szczepański square in front of the Stary Theatre and then marching onto the stage and the auditorium to establish the ultimate order, might point to the anticipation of something completely different from our modern history.” Witold Filler lauded “Dziady” staged in Kraków by Konrad Swinarski for their universal tones, this statement being certainly underpinned by the aversion to Kazimierz Dejmek’s political staging of “Dziady” at the National Theatre. The critic failed to notice the Russian soldiers who in the third act of “Dziady” kept patrolling the auditorium.

The red-starred soldiers coming to Katowice were soon followed by the groups of civilians with sleighs, upon which they would put the remaining goods. The city drew people from Zagłębie. Many of them spoke Russian and would pal up with Soviet soldiers. In the evening, a swarm of plunderers went back home. Towards the end of “Dziady,” the folk lashed out at Konrad. It would strip his clothes and tear them into pieces. And then burst into the Senator’s room. The folk would take closets, tables and chairs with hard backs.

Piotr Zaczkowski,

Director of Katowice Miasto Ogrodów – Instytucja Kultury im. Krystyny Bochenek